Tom Grandy: Determine how your profit will be spent ahead of time

Part 1 of a two-part series.

Gearstd/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

Nearly all dollars a company spends have been predetermined…except profit. Labor and materials dollars are predetermined based on the job. All overhead costs have been directed where to go. Specific dollars have been pre-allocated for rent, utilities, insurance, etc. However, profit tends to be the redheaded stepchild. It sits around until somebody decides to buy an extra tool or perhaps the owner takes a weekend trip with the family. The profit literally gets frittered away until it’s all gone. That needs to change! As Dave Ramsey says, “We need to tell every dollar how it will be spent, ahead of time.”

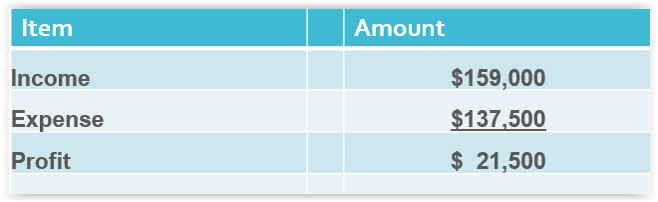

This will be a two-part article. Part I will deal with determining what “real” profit the company has from a cash flow standpoint. The second article will deal specifically with what percentage of the “real” profit should be allocated for what. Profit from an accounting standpoint is far different than the “real” profit viewed from a cash flow perspective. Below is a simplified P/L statement from an accounting perspective.

Obviously, from an accounting standpoint, the company generated a $21,500 net profit or 13.5%. Everything looks great. The bottom line is that the company will pay taxes based on the “accounting” net profit of $21,500. However, there is a slight problem. Additional money flowed out of the company (from a cash flow perspective) that accounting literally ignores. By the way, it’s not the accountant’s fault, the rules are set by the Internal Revenue Service! Your accountant is simply following the rules.

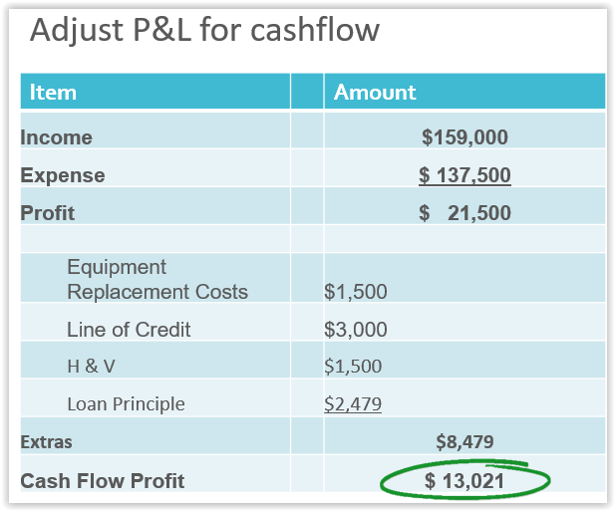

Below, we will discuss what needs to be considered, from a cash flow perspective, to come up with the “real” profit.

- Equipment replacement cost — Depreciation is an accounting term, and it deals with what the company paid for a piece of equipment, and/or vehicle, years ago. Equipment replacement costs deal with what it’s going to cost in the future in order to replace that piece of equipment when it wears out. Let’s assume the vehicle will last the company four more years and it will cost the company $40,000 to replace it four years from today. That means the company will need to build $10,000/year ($40,000/4 years = $10,000) into its overhead in order to be able to pay cash for the new piece of equipment four years from today. Equipment replacement costs are typically 25% to 50% higher than depreciation.

- Debt repayment — Debt can take many forms. It might be repayment of a line of credit, money owed the owner or a family member, or perhaps overdue taxes and penalties. Any principal payments on these items will not show up on the company’s P/L statement, however the dollars actually did flow out of the company.

- Loan principle – Loan payments are made up of principal and interest. The interest shows up on the company’s P/L statement as an overhead expense, but the principle does not. Again, the principle part of the payment really did flow out of the company, but it does not show up on the P/L statement.

- Hill & Valley account — This will be a new term for most readers. The Hill & Valley account is literally money held back for those typical 90 slow days most trades companies incur each year. During those slow times the bills still need to be paid. The Hill & Valley account basically saves money back to cover those slow times. There are two ways to fund the Hill & Valley account.

The first is included here where the company literally picks a dollar figure and treats it like any other bill via putting a specific amount of money back into a savings account each month. We will deal with a second way to fund the Hill & Valley Account next month.

Below, you will see what the companies “real” profit looks like after accounting for the above four items. These are real costs of doing business, and the money literally flowed out of the company, but was not considered from an accounting/IRS perspective.

Note the accounting P/L statement showed a net profit of $21,500 of which the company will be forced to pay taxes on. However, from a cash flow perspective, the “real” net profit (money left in the checkbook) is only $13,021 or a net profit of 8.2%.

We now know what the company’s “real” net profit is. The next step is to predetermine how that “real” profit will be allocated each month. That will be the subject of next month’s article.

Keeping track of dollars is one thing. Keeping track of company policies is quite another. Every company should have a company policy manual that details everything from vacation policies to drug testing. Once created, every employee needs to sign off on it.

However, that takes time, right? Wrong! This month’s website special is our 96-page company policy manual provided in Microsoft Word so the company owner can easily add, change, modify or delete sections in order to customize the manual. The normal investment is $134, but this month it’s only $97. Order today!

Tom Grandy has more than 50 years of experience in industry and small business. He has worked as the general manager of a service company, was regional director of company development for the DIAL ONE franchise and is the Founder of Grandy & Associates.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!