Campus shutdown at Oakland University exposes hidden risks of aging hot-water infrastructure

Failure underscores the critical role of preventive maintenance, plumbers and wholesale supply chains.

Oakland University was forced into an unprecedented, near-total campus shutdown after a failure in its high-temperature hot-water (HTHW) system triggered emergency underground repairs, disrupting classes, housing and campus operations for more than a week.

According to university officials, the underground heating loop which supplies heat and domestic hot water to large portions of campus, developed a significant leak that was initially losing roughly 6,000 gallons of water per day. As temperatures dropped, pressure in the system rose, and the loss rate increased, raising the risk of widespread system failure. University leadership determined that delaying repairs until the end of the semester was no longer safe.

“The lower the temperature, the higher the risk of failure,” administrators told campus stakeholders in announcing the emergency closure.

The shutdown halted almost all in-person instruction, closed multiple academic buildings and support facilities, and forced the relocation of students from several residence halls tied to the compromised loop. Even after the primary leak was believed to be repaired and the system re-pressurized over the holiday break, additional leaks emerged. As of reopening, heat remained unreliable in more than 20 buildings, forcing continued operational adjustments.

The Oakland disruption is far from isolated. Across the U.S., aging plumbing and mechanical infrastructure in public facilities represents a growing and largely invisible risk.

A national infrastructure problem hiding beneath the surface

While there is no centralized national database tracking public-building closures caused specifically by plumbing or hot-water heating failures, federal and academic research confirms that the underlying conditions that lead to crises like Oakland’s are widespread.

A major survey by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that 54% of U.S. public-school districts report needing to update or replace multiple major building systems, including plumbing, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning. In the same assessment, the GAO estimated that roughly 36,000 school buildings nationwide — about one-third of all public school facilities — suffer from HVAC inadequacies.

In a broader infrastructure-condition study published through the National Institutes of Health public research archive, analysts found that 45% of surveyed public-school buildings had at least one “unsatisfactory, nonfunctioning, or critical-failure” rating for HVAC or plumbing systems. Nearly half of schools carried at least one serious mechanical or plumbing defect capable of causing operational disruption.

These findings help explain why failures like the one at Oakland University are becoming more common across educational, municipal and healthcare facilities. Underground distribution loops, central hot-water systems, aging pipe networks, and custom mechanical assemblies often remain in service for decades, long after their original design life.

The cascading impact of one hidden failure

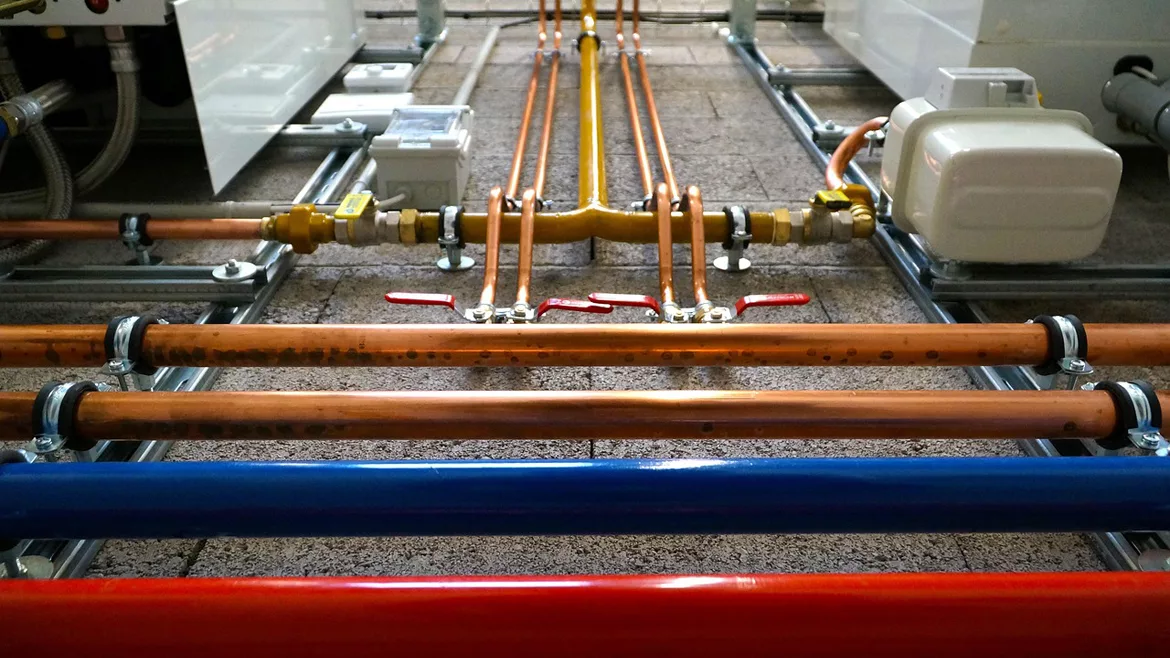

At Oakland, the infrastructure at risk was largely invisible to the campus community until it failed. HTHW systems are rarely seen, but they are essential to winter operations in northern climates. When compromised, they become single points of failure capable of idling entire campuses.

University officials acknowledged that replacing aging HTHW components is not simple. Some of the system parts are no longer readily available off-the-shelf, requiring custom fabrication that can extend lead times from days into weeks. In Oakland’s case, administrators indicated that standard replacement components could take up to nine weeks to arrive without local sourcing.

Why plumbers and wholesalers are central to prevention

For the plumbing and mechanical industry, the Oakland shutdown is a vivid reminder that preventive maintenance is not optional infrastructure spending; it is a form of institutional risk management.

Plumbers, pipefitters, and mechanical contractors serve as the frontline defense against systemic failure. Their expertise in pressure testing, ultrasonic leak detection, corrosion assessment, and lifecycle replacement planning often determines whether a system is proactively stabilized or allowed to deteriorate until rupture.

Equally critical are wholesalers and manufacturers that supply the pressure-rated pipe, valves, fittings, insulation systems, pumps, and controls that allow repairs to happen quickly and safely. When institutions rely on proprietary or aging components that are no longer stocked, emergency repairs become exponentially harder to execute.

The GAO and NIH-supported research make clear that tens of thousands of U.S. public buildings are already operating with compromised plumbing and HVAC systems. Oakland University’s emergency closure is a warning about what happens when aging infrastructure, limited redundancy and delayed upgrades collide during peak demand.

For building managers, the lesson is stark: underground heating and hot-water systems demand the same capital-planning rigor as roofs, electrical systems, and life-safety infrastructure. For wholesalers and manufacturers, the event underscores the need for inventory depth, rapid-response sourcing and technical support for legacy systems. And for the plumbing and mechanical trades, it reinforces a truth long understood in the field — when plumbing fails at scale, communities stop functioning.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!