Renewable Heating Design | John Siegenthaler

Using ratios to measure, compare and improve HVAC systems

Relating to ratios

During my early high school years, I dreaded math class. I got by - but barely. Mathematics just seemed like some pointless “game” with lots of rules. I didn’t see any usefulness in doing things like factoring a trinomial, or memorizing the law of cosines. I failed algebra in the 9th grade.

Things began to change in eleventh grade. I was fortunate enough to have a teacher who began showing how to apply math to some simple problems in the “real” universe, rather than “mathmagic land.” Simple tasks like laying out a precise 90º angle using 3/4/5 or 5/12/13 measurements, or calculating the amount of concrete needed to fill oddly shaped spaces. I ended up taking calculus my last year in high school followed by three years of calculus in college. I did well in those years, but I admit that much of what I do as an engineer doesn’t require high level math.

Now I get it

Over the years, I’ve come to appreciate math as a “tool” to help predict how the physical world behaves and how to measure that behavior. Occasionally that involves complex mathematics, but many times very simple math can be used in design or performance measurements of HVAC systems. One example is the simple concept of a ratio, where one physical quantity is divided by another.

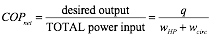

Many of the ratios used in the HVAC industry are just some “desirable output” quantity divided by the “necessary input” quantity. One example is the coefficient of performance (COP) of a heat pump. The desirable output quantity is Btu/hr of heat output. The necessary input quantity is the electrical input power needed to operate the heat pump. The latter is typically measured in watts or kilowatts.

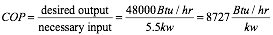

Consider a heat pump that delivers heat at a rate of 48,000 Btu/hr. This is the desired output quantity. Assume that the necessary input quantity was 5.5 kilowatts of electrical power to operate the heat pump. If we put these values into a ratio for COP we get:

Formula 1:

Those familiar with heat pumps recognize that this number is very different from COP listings in heat pump rating tables, etc. The reason is the units. We’ll take care of that in a minute, but before that lets interpret the units following the number 8727 in formula 1. They mean that - under this specific operating condition - the heat pump is producing 8727 Btu/hr of heat output per kilowatt of electrical power input. Although that interpretation is “valid,” it’s definitely not customary. To get this COP into customary form, it’s necessary to convert the units of kw in the bottom of the ratio into Btu/hr. This is possible because both kw and Btu/hr are valid units for the same physical quantity - power. Here’s the conversion:

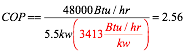

Formula 2:

The number and units in red are a conversion factor that changes kw into Btu/hr. This conversion factor just means that 3413 Btu/hr is equivalent to 1 kilowatt of power.

Over the years, I’ve come to appreciate math as a “tool” to help predict how the physical world behaves and how to measure that behavior. Occasionally that involves complex mathematics, but many times very simple math can be used in design or performance measurements of HVAC systems.

Processing all three numbers in formula 2 through a calculator yields a value of 2.56. Just as importantly, the units in formula 2 all cancel out algebraically (i.e., the units Btu/hr in the top of the ratio cancel with the units Btu/hr in the bottom of the ratio. Same for the units of kw). This makes the number 2.56 “unitless.” Simply stated, the COP of a heat pump, expressed in customary form, always yields a unitless number. That means the number is valid regardless of the unit system used to generate it. A heat pump operating with a COP of 2.56 means exactly the same thing in the US, Canada, the UK, Argentina or any other place. When expressed in customary form (e.g., where all the units in the top and bottom of the ratio cancel out), there’s no such thing as a “metric” versus “imperial” value of COP.

How good is it?

When a ratio is defined as some desirable output divided by the necessary input, the higher the resulting number (e.g., after dividing the top number by the bottom number) the “better” the desired effect. A heat pump operating with a COP of 3.0 is performing better - from the standpoint of efficiency - than a heat pump with a COP of 2.56. Since most ratios used in HVAC systems are defined as a desirable output divided by a necessary input, high numbers are better than lower numbers. Common examples of such ratios in the HVAC industry are EER, SEER, COP, HSPF, boiler efficiency and distribution efficiency. The latter is particularly relevant to hydronic systems, and defined as follows:

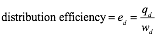

Formula 3:

Where:

ed = distribution efficiency

qd = heat delivery rate of distribution system at design load (Btu/hr)

wd = power to operate distribution system at design load (watts)

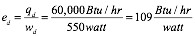

Consider a forced-air distribution system in which the blower on the air handler draws 550 watts, to deliver a thermal output of 60,000 Btu/hr. The distribution efficiency of that system would be:

Formula 4:

A distribution efficiency of 109 Btu/hr/watt means that this particular distribution system can deliver 109 Btu/hr per watt of electrical input to operate the distribution system.

Distribution efficiency has nothing to do with the type of fuel used, or what converts that fuel into heat. It only pertains to the ability of the distribution system to move heat from where it’s produced to where it’s needed in the building.

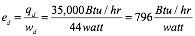

To form an opinion on how good this distribution efficiency is it’s necessary to have something to compare it to. How about a hydronic system (a real one) that delivers 35,000 Btu/hr using only 44 watts of electrical power input to its circulator. Its distribution efficiency would be:

Formula 5:

The hydronic system is delivering 796 Btu/hr per watt of electrical input. That’s over 7 times higher than the distribution efficiency of the forced-air example. The simple ratio used to define distribution efficiency reveals a major advantage of hydronic-based thermal delivery compared to air-based delivery.

Relative Effects

Other ratios of interest in hydronic system design compare the importance of two entities that effect the same physical situation. A good example is something called Reynolds number, which is defined as follows:

Formula 6:

Where:

Re# = Reynolds number (unitless)

v = fluid velocity (ft/sec)

d = diameter of pipe (ft)

D = density of fluid (lb/ft3)

u = dynamic viscosity of fluid (lb/ft/sec)

You might be wondering - why would anyone create a formula that combines all these different physical quantities? The answer again is based on the concept of a ratio. The Reynolds number represents the ratio of the inertial forces acting on a fluid divided by the viscous forces acting on the fluid. When the inertial forces are dominant the fluid flow is turbulent. That condition is desirable for good convective heat transfer, such as between the fluid and the internal surfaces of a heat exchanger. Experiments performed long ago showed that turbulent flow occurs when the Reynolds number is over 4000. When the viscous forces dominate, the flow will be laminar, which is not conducive to good heat transfer. This happens when the Reynolds number is less than 2300.

You’re probably wondering what happens to the flow when the Reynolds number is between 2300 and 4000. This is a region of instability. The flow could be either turbulent or laminar, and it can change between these two conditions. It’s generally a condition that should be avoided when heat transfer is important. The way to avoid it is to calculate the Reynolds number that would occur in a proposed design and make sure it’s well above 4000.

The quantities needed to calculate the Reynolds number in formula 6 are given in specific units. When these units are put into the formula, they cancel each other out algebraically. That’s why the resulting Reynolds number is “unitless.” It’s just a number with no units. If, for any reason, the quantities used to calculate the Reynolds number don’t allow all units to algebraically cancel out the resulting calculation is invalid. This is something that should always be checked when calculating a Reynolds number.

Definitions are important

There are hundreds of other ratios that could be discussed in the context of HVAC systems. New ones appear from time to time, often defined based on work at the US Department of Energy, as a way to express the efficiency of an appliance that uses energy to produce some intended effect. In most cases, these ratios are derived from the fundamental concept of a desirable output divided by the necessary input, but with very specific definitions for what constitutes the desired output and the necessary input.

It’s important to know exactly how a ratio that represents the performance of a device is defined. COP is a good example.

Consider that a geothermal water-to-water heat pump requires flow through its evaporator and its condenser whenever it operates. In almost all cases, this flow is created by circulators, which require electrical power to operate.

So, should the COP rating of a heat pump include the power input to operate the circulators? It depends on how the COP is defined. If the definition only includes the power to the heat pump and not to any external devices needed for it to operate, then no, the circulator power is not included as part of the necessary input. This might be the case when the heat pump is run on a test stand in a lab. However, after the heat pump is installed, the person who pays for its operation also has to pay to operate the required circulators. From their perspective, the “net” COP that best describes the true operating cost merit of the heat pump would include the cost of operating the heat pump and the circulators. Thus, the “net” COP of the heat pump could be defined as:

Formula 7:

Where:

COPnet = defined net COP of the heat pump & circulators combined (unitless number)

q = heat output rate from heat pump (Btu/hr)

wHP = power input to operate the heat pump (watts)

wcirc = power input to operate the circulators required for the heat pump (watts)

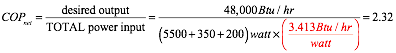

Here’s an example. Assume that the same water-to-water heat pump described early outputs 48,000 Btu/hr while drawing 5.5 KW of electrical power. The earth loop circulator associated with the heat pump requires 350 watts, and the distribution circulator carrying heat away from the heat pump requires 200 watts. The “net” COP of operating this heat pump would be:

Formula 8:

The power input to the heat pump (5.5 kw) was converted to 5500 watts so it was in the same units as the power required for the circulators. The conversion factor shown in red in formula 8 changes watts to Btu/hr. This allows the units of Btu/hr to cancel out betweene the top and bottom of the ratio.

In this example the “net” COP of 2.32 is about 10% lower than the COP of 2.56 associated with just the heat pump.

I like the concept and definition of net COP because it reflects the true operating cost merit of the installed heat pump, rather than the COP of the heat pump combined with an implication that the necessary flows are created for free. The takeaway: when comparing COPs or any other performance metric be sure you understand exactly how that metric was defined. Ask the old adage goes: don’t compare apples to oranges.

Many of us in the HVAC industry use ratios every day. Perhaps without giving it much thought. They’re one of the simplest mathematical concepts, yet they give us insight and the ability to compare design options and equipment performance. They also provide a way to communicate the relative merit of competing options.

If only I had seen all this coming back in 9th grade…

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!