Articles by John Siegenthaler, P.E.

Hydronics Workshop | John Siegenthaler

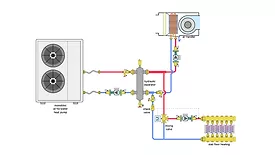

As air-to-water heat pumps replace boilers in North American hydronic systems, designers must rethink traditional approaches to heat transfer, or risk costly and inefficient installations.

Read More

Renewable Heating Design | John Siegenthaler

Transitions: Systems for simultaneous heating and cooling (Part 2)

What happens if there’s a simultaneous call for domestic water heating and cooling?

June 9, 2025

Renewable Heating Design | John Siegenthaler

Transitions: What do I do about cooling? (Part 1)

May 28, 2025

The Glitch & The Fix: May 2025

Hydronic heating glitch solved: Why adding a circulator won't fix primary loop flow issue

Cut & cap

May 8, 2025

Hydronics Workshop | John Siegenthaler

Using hydronics to leverage time-of-use electrical rates

Buying low

May 2, 2025

Renewable Heating Design | John Siegenthaler

Versatility in direct-to-load systems, part two

Going direct.

April 8, 2025

The Glitch & The Fix: April 2025

Unexpected results: heat pump system at low outdoor temperatures

Consider the “dual temperature” heat pump system shown in figure 1

April 4, 2025

Hydronics Workshop | John Siegenthaler

Build what you need: Availability and customization of heat pump systems opens doors of possibilities

April 2, 2025

The Glitch & The Fix: March 2025

OK - At a glance: three zone radiant floor heating system

March 31, 2025

Renewable Heating Design | John Siegenthaler

Versatility in direct-to-load systems, part one

Going direct.

March 12, 2025

Keep your content unclogged with our newsletters!

Stay in the know on the latest plumbing & piping industry trends.

JOIN TODAY!Copyright ©2026. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing