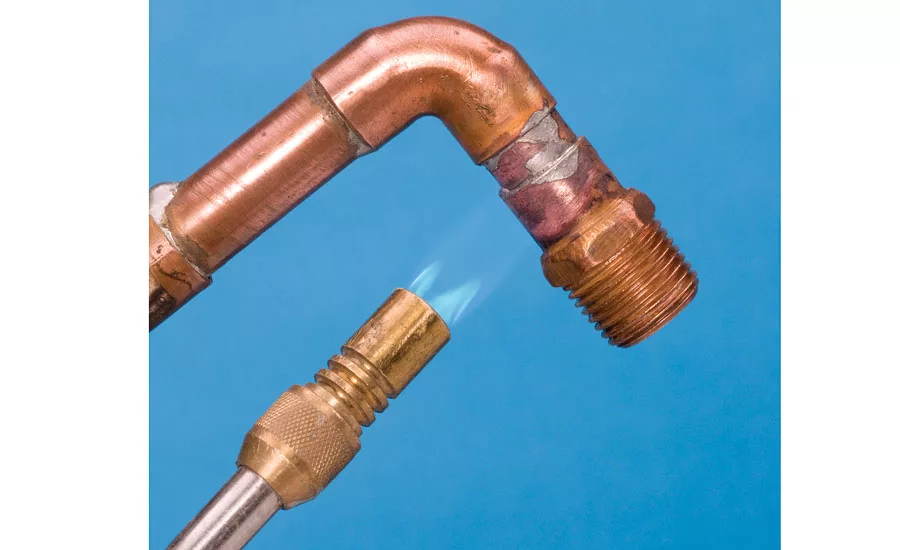

Soldering vs. brazing when piping is involved

As for the HVAC system, brazing is definitely necessary.

If you have ever been involved in medical gas piping or refrigeration piping, brazing is where it’s at when joining copper tubing. On the plumbing side, we tend to solder copper tube joints when using a torch.

When looking for a stronger joint, brazing is one of the options. In addition to medical gas and refrigeration tubing, brazing is common in water piping and fuel gas piping, to name a few systems.

Over the past few years, I have noticed brazing has come under attack. The easiest way to attack a brazed joint is to blame the contractor making the joint. But is the contractor really at fault?

First things first, there is often confusion as to when a joint is brazed vs. when it is soldered. The definition of brazing is a joint made with a temperature in excess of 450° C. We don’t use centigrade or Celsius in the United States, so translating that temperature, it comes to approximately 840° F.

Most contractors think of brazing as a joint made at temperatures greater than 1,000° F. In many ways, both temperatures are correct. While the definition is approximately 840° F, the brazing rods used in plumbing, medical gas and refrigeration are all greater than 1,000° F.

You could say the problem in brazing originates from soldering. That might not make sense, but realize that, before we learn to braze, we learn to solder. When we braze, we tend to think it is glorified soldering, just with a stronger filler metal.

That is not exactly true. One of the issues long plaguing our profession has been the fittings we use for brazing. The fittings have traditionally been solder fittings. That means the cup length is designed for solder. When you have a stronger brazed joint, you don’t need the full depth of the solder fitting. Of course, we always try to fill the entire cup with brazing filler metal, which can lead to problems.

The cup length, or socket depth, for a brazed joint needs to be no more than half the depth of a solder fitting. You may be asking, “Why do we continue to use solder fittings for brazing?” The reason is that, up until recently, there were no special brazed fittings. That all changed with the greater acceptance of a relatively new standard for brazed fittings, ASME B16.50. While the first edition of the standard was issued in 2001, it took manufacturers a while to adapt to producing special brazed fittings.

The biggest change to the fittings is the socket depth or cup length. To give you a comparison, for a 1/2-in. solder fitting, the socket depth must be a minimum of 1/2 in. For a 1/2-in. brazed fitting, the minimum depth required is 0.22 in.

When the fittings get larger, the difference becomes more noticeable. For a 2-in. solder fitting, the socket depth must be a minimum of 1.34 in. For a 2-in. brazed fitting, the minimum socket depth is 0.40 in. The shorter cup fittings make it easier to get a good brazed joint. You don’t need the solder depth to make a strong brazed joint. Hence, some of the joining problems will disappear. The brazing will go much faster since you don’t have to try to fill the entire cup of a solder fitting.

In the field, there is anecdotal evidence shorter socket fittings result in less chance of having a cracked and leaking brazed joint. Typically, the cracked filler metal leaking joint occurs a few years after the brazed joint is made.

Copper oxide formation

Another major issue with brazing is the formation of copper oxide on the inside of the pipe. If you look at a brazed joint on the outside of the copper tube, it looks ugly and black. That black is copper oxide formed by the presence of copper and oxygen. If there is oxygen or air on the inside of the copper tube, the same black stuff will appear on the inside wall of the copper tube. That is not a good thing to have inside the tubing.

HVAC and medical gas technicians have been trained for years to only braze when the pipe and fittings are filled with nitrogen, sometimes called oxygen-free nitrogen or OFN. If you purge the piping of air and fill the inside with nitrogen or OFN, you will not have the formation of copper oxide on the inside of the pipe when you braze. Since there is no oxygen, there can be no copper oxide. Just simple chemistry.

So before you braze, think nitrogen, think purge. You need to keep nitrogen running through the pipe at very low pressures while brazing a joint. That means a small opening point of escape at the end of the piping system to allow the nitrogen to continuously flow at a very low rate. This will keep the copper tube shiny bright on the inside, rather than black and gunky.

The use of nitrogen is second nature to an HVAC or medical gas piping technician. It seems strange to someone who works solely in the plumbing profession. The last things you want on the inside of the pipe are particles that can break off into the piping system after the system is placed in service. If you think you can flush any copper oxide out of the pipe before placing the system into service, think again. You never get all of it. You need to run OFN when you are brazing.

One question about the difference between soldering and brazing is the final strength of the joint. Yes, brazing is a much stronger joint, capable of handling much higher temperatures and pressures in the piping system.

I am often asked if brazing is really necessary for HVAC and medical gas piping systems. For medical gas piping systems, the answer is no, soldered joints can easily handle the temperatures and pressures in a medical gas piping system. The reason we braze is because the medical profession wants an extremely secure, strong joint.

As for the HVAC system, brazing is definitely necessary. The temperatures and pressures in many refrigerant piping systems exceed the rated pressure for solder joints. We don’t want to have refrigerant leaking into the atmosphere. So brazing is a must.

If you choose to braze copper tube in a plumbing system, it is simply because you want a stronger joint. Soldering, as well as other joining methods, can handle the temperatures and pressures anticipated in typical plumbing systems.

Follow the rules for brazing, using the newer shorter socket depth fittings. Who knows, they may stop placing blame and switch to praising the contractor for excellent leak-free brazed joints.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!